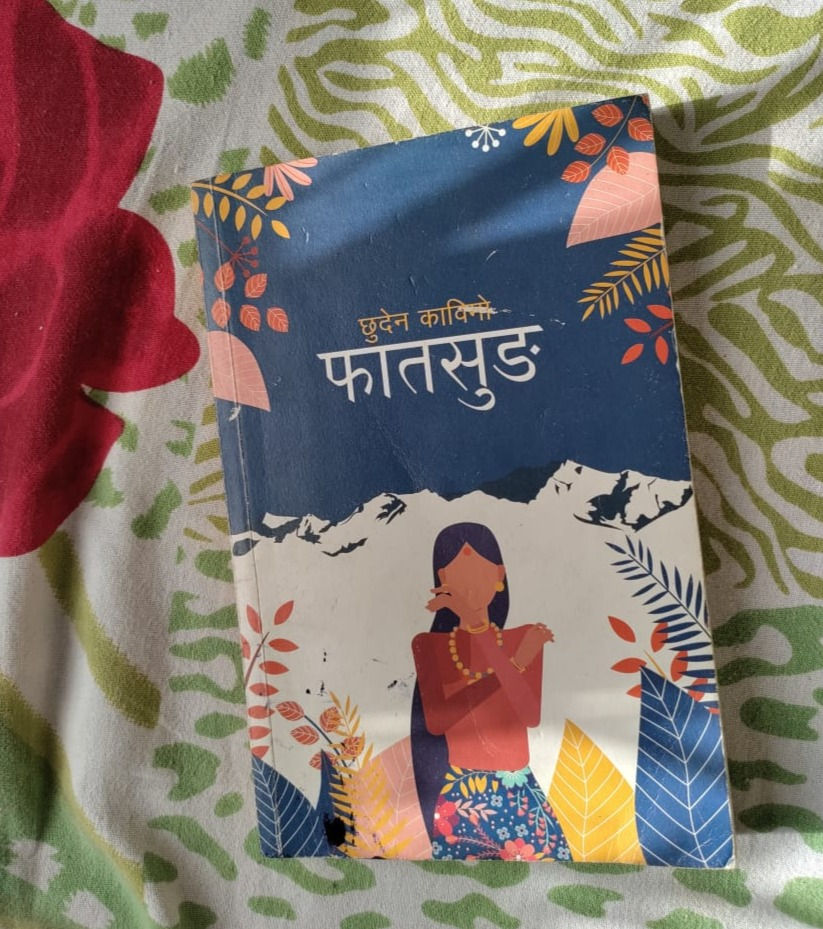

फातसुङ - The Song Of The Soil

- Simran

- Sep 21, 2022

- 4 min read

The Gorkhaland agitation of 1986 is one of the most important movements of Sub-National self-determination which transpired in the Darjeeling and Kalimpong Hills. A mass movement to form a separate state under the Indian Union under the leadership of Subash Ghisingh faced suppression by the then government of the Community Party of India (Marxist) when Chief Minister Jyoti Basu was in power in the state of West Bengal. The movement ultimately led to the creation of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council, a semi-autonomous administrative body on 22 August 1988.

The Gorkhaland movement of 1986 witnessed mass participation from the youth, organized into the Gorkha Volunteer Cell (GVC). In Kalimpong, Chattrey Subba was at the forefront of one faction of GVC.

Those that remember Chyasi ko Andolan or the revolution of 1986 recall it as a period of fear and pain. Almost every family and village in Darjeeling has an anecdote about 1986 and it is seldom devoid of violence and grief.

In Fatsung, the events of 1986 unfold as a memory of bygone days. The story follows Ripden and the narrator on a journey to find Ripden's long-lost father, who vanished after 1986. The duo then encounters an old survivor of the time, who recounts the happenings of the 1986 Andolan.

As the narrator travels to his native village in Malbung to document the passing of his childhood friend, Ripden, in a tragic landslide, he evocates his memories of school days, his village, and his friends. Using a simple and humorous voice, typical of Darjeeling's language, the author points out subtle socio-political dynamics of the present day. The English translation of Fatsung, named Song of the Soil preserves the humorous voice of hope and despair and the succinct story-telling style of the original, thus making for a gripping and tragic read.

'"Sainla Baje dies because of drink. So, I don't like the villagers getting drunk. Nor do I like them selling their land to get drunk."

"Three months after he disappeared, a shakha branch, of the Rastriya Swayamsewak Sangh was set up on the school playground."

As the novella progresses, we are allowed into the space of the youth of 1986, particularly from the GVC Faction of Chandra Singh Subba. Young boys who had probably just wanted to skip math tuition suddenly find themselves manufacturing crude bombs to fight state forces. Even as these characters grow up through the thrill of a revolution, they succumb to personal losses and resentment. It is the nature of things that when violence intervenes in a community, it gradually takes up space as deeply personal embitterment.

"We won’t pick a fight with other boys from now on. We will fight against the CPI(M)."

But that is not to say that there was no free will in these young foot soldiers' participation in the movement. It is also the nature of things that when citizens are left to cope with socio-political neglect, resentment is bound to be brimming. The 1986 agitation was hardly an abrupt overnight adventure. The demand for the right to self-determination for the people of Darjeeling hills is a long-standing one documented as early as 1909 when the Hillmen's Association appealed for a separate administrative setup for Darjeeling to the Morley Minto Reforms. So what fueled violence in an otherwise diplomatic political movement, and what led it astray?

"Every night in his dreams he would run like the hero of Rambo, carrying a gun."

"The land on which his hut stood, that land should belong to him. He could live with that small dram. He could die for it too."

Even as the fighting escalates between the GNLF and CPIM cadets, revolutionaries, and the CRPF to culminate in infighting between the two factions of the GNLF, we get glimpses of lesser-known narratives of loss and tragedy.

What I found most remarkable about Chuden Kabimo's observations is his attention to the inconsequential moments within the revolution. Such fleeting moments of human vulnerability add layers of emotion against the violent unfolding of events. The author articulates the characters' nostalgic longing for Home, their encounters with love, and hopes and dreams of family. From homes being lost to landslides or set on fire amidst the revolution, the author questions identity and belonging by emphasizing the symbolism of Home and dreams.

"When a house burns down, it does not merely mean thatsome pieces of wood have been set on fire, or that stones and mud have been left to smolder. It means that an entire world has gone up in flames. Faith itself has gone up in flame. Belief has gone up in flames. Possibilities have gone up in flames. One’s self has gone up in flames."

The Covid-19 Pandemic taught me a term called 'collective grieving'. When violence crashes into our lives, it leaves behind afterwaves of grief that get carried on for generations. Via the subplots of Shahid Ram Prasad, Budhathoki’s daughter, Neptay, and the narrator himself, Fatsung consolidates the personal grievings of the surviving characters of 1986. In holistically covering narratives, the author points at the larger impact on the masses of conflict and deceit orchestrated by a powerful few.

*The English translation of फातसुङ, Song of The Soil, by Ajit Baral (edited by Anurag Basnet) and published by Rachna Books, Gangtok has been long-listed for the JCB prize 2022. It is the first Nepali book translation to make it to the long list of the award.

Comments